World reknowned linguist Noam Chomsky will go down in history for his ‘universal grammar’ (UG) theory, with its linguistic ‘deep structure’ contained within a cerebral ‘language acquisition device’ (LAD).

Chomsky is an ‘innatist’, or ‘nativist’, believing that a language ‘instinct’ is embedded in the structure of all homo sapiens minds. Babies are born, innatists believe, ready to sponge up language, because fundamental grammatical structures are already in place, in minds, prior to births. Cerebral ‘language acquisition devices‘, termed as such by Chomsky, enable this sponging up of language once babies are born. Personally, I prefer the term ‘facilities’ to ‘devices’. But Chomsky also used the metaphor of a ‘black box‘ to describe how children, during an early ‘critical period of language development‘ (from birth to puberty) could know so much, so quickly, when language input at their young, tender ages is so sparse. That knowledge, he argued, is supplied by the contents of the metaphorical ‘black box’: His ‘poverty-of-the-stimulus‘ argument.

There is plenty of evidence to support Chomsky’s ideas and for linguists this is very persuasive, being steeped, as these ideas are, in highly complex linguistic analyses – on which Chomsky is the expert.

But, in stepping outside the linguistics box, the childhood language acquisition story takes numerous twists and turns. Other opinions exist to explain the remarkable rapidity with which children learn their mother tongue languages. In brief, opposing arguments look to what goes on outside children’s minds, rather than inside.

First must be mentioned the behaviourist perspective. I say first, because reacting to the Pavlovian, stimulus-response pedagogy of behaviouralism, as developped by B.F Skinner (1957), was Chomsky’s original intellectual stimulus (1959). He didn’t agree at all with this pedagogical method. Primary language learning (L1), he said, was a process of ‘mentalese‘: A mental activity performed by the internal hardware of the brain; the neurological mechanics of which were already in place at the moment of birth, in the metaphorical ‘black box’.

Indeed, within the realm of ELT and secondary language learning (L2), behaviouralism, with its focus of learning by rote (e.g. audio-lingual’s ‘listen & repeat’) has largely fallen out of favour. It is now generally agreed that languages are far too complex to be learnt parrot style. Creativity and improvisation, through discourse (‘the communicative method‘), has become the more accepted approach employed by language teachers, with Steve Krashen’s ‘comprehensible input theory‘ (1977) continuing to provide the blue-print: Krashen’s theory focusing more on the exterior, social input to language acquisition’ (primary & secondary) than Chomsky’s focus on cognitive factors.

This brings us back to an earlier, second take on behaviouralism. This came from the French child psychologist: Jean Piaget (1936). Children’s brains are formed through stages of maturation, claimed Piaget, in which children acquire language through social interaction and not through some ‘language acquisition device‘. From the starting block of birth, learning occurs a posteriori, in developmental steps.

Incidentally, consider the contemporary neurological perspective: Intellectually speaking, babies are born too early. This is an evolutionary by-product of bipedalism, which affected the morphology of female pelvises and birth canals. Once born, babies’ brains still need time to fully function. In biological terms this is largely due to the process of ‘myelination‘: The building up of a fatty deposit on the outside of neurones for the transmission of neural messages. For a metaphor, think of plastic cabling around electrical wires. This biological process proceeds as babies develop into children, as the neurones make connections and link up, according to whatever cultural environment they are born into.

The difference between Chomsky’s and Piaget’s analyses led to the famed ‘Chomsky/Piaget debate’, held at a conference in Paris, 1975. The term ‘debate‘, according to Chomsky, being more of a publishers’ marketing tool. A ‘friendly discussion’ may be more appropriate.

In viewing this second take on behaviouralism (plus Krashen’s social interaction viewpoint) we now encounter the terms ‘evolution’ and ‘cultural environment’. These are terms on which any Chomskyian linguistic analysis does not take into account; as several researchers in this field of enquiry have previously noted. Steve Pinker, for example, whilst going a long way in following innatist theories, notes Chomsky’s omission of evolutionary perspectives e.g. Darwinian theories concerning natural selection.

To evolutionary psychologists, this is a major omission. John Dunbar (2007), for example, explores the metaphor of baking a cake. The final cake is a result of the ingredients and the hot oven (‘cultural environment’) into which it is placed. So it is with language, and psychological developments, embedded as they are within cultures. The extensive library of books and articles exploring the symbiotic relationship between language and culture provides a vast acreage of supporting documentation.

Besides, as neurologist Terence Deacon argued (1997), young children quickly learn to use computers, through a process of trial and error, with no inkling of any computer programming language. These are embedded deep within the computers ‘mind’; not the minds of children. ‘Mentalese by proxy’, we could say. This is not to dispute Chomsky, but to suggest that the languages we use to speak and write are the communicative interfaces. Only computer experts and linguists understand ‘how’ they work. This knowledge is not necessary in our daily lives. Indeed, Terence Deacon takes this one step further and argues that languages themselves evolve to facilitate ease of use, just as computer interfaces become increasingly user-friendly. Indeed, they evolve and are passed on through the bottleneck of childhood. ‘Parasitic viruses’ is the metaphor he uses to describe the way in which languages attach themselves to children, and mutate, in order to survive.

It is, perhaps, therefore, a clichéd truism to say that we (homo sapiens) are an admixture of ingredients (biology, genetics, morphology, neurology, language) blending and transforming in the cultures (ovens) within which we are born and grow up. The evolutionary aspect to this tale is that cultures and environments change over time. To be more precise, over extraordinary long periods of time. Recent studies by neuro-palaeontologists are placing the onset of language with homo ergaster circa: 1.7 – 1.4M yrs bp (before present). (see here)

The big revolutionary linguistic breakthrough, for homo sapiens, in distinguishing their language potentials from those of other life forms, including primates, came about during the mid-paleolithic period (200K – 45K bp), or – the ‘tectonic phase‘ (Renfrew, C. 1996); many thousands of years after homo ergaster became the first language using hominid. This was a time when the symbolic potential of language came to its fore (homo symbolicus. Cassirer, E. 1944); as explored in more detail in a previous blog (see here).

Similarly, I have previously explored research into language and the neurology of the brain (see here), which itself has a long history. Inter-disciplinary considerations of linguistics, cultural environments, evolution and neurology provide us with a more rounded picture of our special, homo sapiens species-specific language attribute that sets us apart in the animal kingdom.

In terms, then, of the evolutionary perspective (as per this blog), there have been four major environmental changes in the long history of the evolution of homo sapiens from its hominid ancestors.

- Changing natural habitat within Africa in which our more primate form ancestors descended from the trees and developed bipedalism to search for food on the plains.

- Savannah living. The control of fire and discovery of cooking, along with the development of stone tool making, which lead to greater calorific intake and increased brain size.

- Mid-paleolithic climate change & ice age. The symbolic use of language

- . The agricultural revolution: Farming. The Neolithic Age.

Avoiding the great explosion of art and technology seen during the upper-Palaeolithic, it is now to the last point on this list that I turn.

Agriculture transformed societies. Through natural selection, following Darwinism, those who were more adapted to this new life-style survived and passed on their genes to their off-spring.

This feedback loop between culture and genetics is most clearly seen with the advent of pastoralism. Prior to pastoralism homo sapiens were ‘lactose intolerant’. Most animals lose their lactose tolerance after weaning, and many people, in different cultures, continue to be lactose intolerant today. But with the arrival of animal husbandry, particularly for those bands of wandering nomads on the Eurasian Steppes (Anthony, D.W. 2007), those few individuals with the genetic make up to be lactose tolerant could digest milk, (probably through the intermediary step of eating cheese). They survived statistically better than their lactose intolerant neighbours and this genetic modification was then passed on through their genes.

This is a biological example.

Humans, like all living species, adapt and modify according to their cultural environments. But this is not such a cut-and-dried affair. On the large historical scale, pastoralism and agriculture are relatively recent: only 10,000 years ago. Furthermore, not all global cultures change at the same time, or in the same way.

The picture, therefore, is complex. Whilst research continue to unravel this story, evolutionary psychologists focus on the distinctions between the ‘hunter-gather’ communities, the farming and the pastoral communities. The life-styles, the cultures, and the outlooks on life were quite different. Anthropological research into modern day hunter-gather, farming, and pastoral communities proves invaluable because, prior to the ‘invention of farming’, all homo sapiens were hunter-gathers’, and a number of these communities continue to exist today.

According to evolutionary psychologists, cultures and psychologies differ according to environments. Just as lactose tolerance developed as a result of pastoralism, subsistence methods and psychological profiles developed in accordance to environments in which humans lived. This is applying the principles of natural selection. Adapt to survive. Survive to pass on your genes.

Perhaps rightly so, Noam Chomsky (here at 92 years) remains cautious about accepting the theories of evolutionary psychologists, for the genetic under-pinings are complex and not yet fully understood. Links between genetic make up and personal characteristics are not on solid ground. Likewise, though the ‘language gene’ FOXP2 was announced a couple of decades ago, it quickly became held in suspicion. So, the picture of ‘language’, evolution and personal psychologies is far more complex than finding a simple location of a gene on a chromosome.

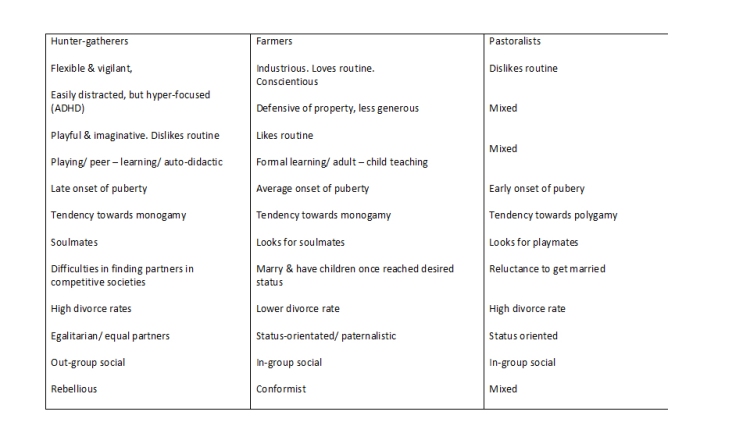

However, whilst not completely understanding the mechanics, the end result can be observed. Anyway, who needs to understand the mechanics of a car to drive? Hence, see here some observable data:

Adapted from: Hofer, A. Evolutionary psychology. The missing piece.

Adapted from: Hofer, A. Evolutionary psychology. The missing piece.

This makes sense. Hunter-gatherers need to be highly vigilant and hyper-focused in their stalking and foraging. At the same time their attentions need to be easily distracted as new potential prey, or dangerous predators, arrive. Farmers, on the other hand, need to be more routine-based, structuring their days to daily tasks, upon which they need to teach their children as soon as they too can become active. Pastoralists form a middle-ground in not completely settling down: Tied to fixed village-based communities, yet tied to their herds which may need to roam far and wide in the search of food and water.

On a moments reflection, as a male homo sapiens brought up in an industrialized, modern, Western European country, I certainly see elements of hunter-gatherer in me. However, if there is any connection of personality types to genetics, then I have surely inherited genes from all three types: Hunter-gatherer, farmer, pastoralist.

How does this relate to pedagogy?

Schooling that expects pupils/students to conform, to follow lesson routines, to be teacher-centred – suit those with the farming-type personalities. This is the schooling that traditionally has dominated education in western societies. Hunter-gather-type personalities can have great difficulties fitting in to this style of educational regime. These are the ‘problematic’, rebellious students. These are the students that Hofer defines as ‘orchids‘. Either they can be extremely talented, hyper-focused, creative auto-didacts. Or, if made to conform, they can wilt, not fit in and show symptoms of attention deficit hyper-activity disorder (ADHD. See chart).

Instantly, this brings to mind the famous TEDtalks by Sir Ken Robinson (2006): Do schools kill creativity? (see here). It was a talk in which Sir Ken Robinson asked schools and educators to re-evaluate their pedagogy in order to bring out the best in children by not stifling energies and creativities. By allowing those ‘hunter-gatherer’ orchid-type minds to bloom and flourish, and not to wilt.

Sir Ken’s talk had the desired effect. New radical ideas have been introduced into mainstream teaching. And they are still being introduced to help the current generation of school children gain today’s, and tomorrows, 4th industrial revolution skills.

Within ELT, the trend has increasingly been towards student-centred teaching. This is ‘the communicative method‘. This is ‘task-based‘ and ‘project-based‘ learning. This is the adoption of AI technologies into the ELT classrooms. These are approaches far away from learning grammar rules and vocabulary lists by rote in front of a teacher standing in front of a black/whiteboard. This is all a result of responding more closely to the way children, and adults, learn better.

For some, the farmer-types, conformity and structure may work better. They have their own valued contributions to make towards the smooth functioning of societies.

For others, the hunter-gatherer types, let them roam free, get distracted and become hyper-focused. Then their individual strengths and creativities will shine.

Phil April 2020.